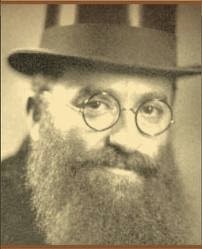

Yossele Rosenblatt

Now consider Rosenblatt's rendition. Opening with a simple ascending minor triad on the words "Rachem no," extending the word "no" (please), Rosenblatt humbly and passionately pleads to God for mercy in restoring Jerusalem, his frequent employment of the sharp 4 scale degree of the Ukrainian Dorian mode adding to the pleading nature of his prayer. After the first verse, Rosenblatt returns to the opening words, "Rachem no" in the relative major, possibly adding a sense of hopefulness to his entreaty, in addition to raising the intensity by singing in a slightly higher register. He again holds out the word "no" and then repeats it several times in a descending motion. He continues chanting the first verse in a accelerated fashion in which I hear a sense of impatience, as if to say, "Come on! NOW!" In reciting the words "the holy Temple that is called by God's name," Rosenblatt musically shouts out the words "shenikra! shimkha!" jumping the octave on each word before falling from the top note. In singing these words in such a fashion, it is as if Rosenblatt himself is calling out God's name in his heavenly appeal.

All of this is, of course, conjecture. The Ukrainian Dorian mode does not necessarily imply a plea, the major scale does not inherently mean hope, and there is no way for me to know for sure that octave jumps indicate Rosenblatt's calling out to God. But what is clear is that Rosenblatt is singing the text of the prayer, choosing notes, rhythms, dynamics, and vocal inflections to communicate the meaning of the words he is reciting.

To try to describe the rest of the setting in detail would take volumes. Musically, it is beautiful and varied. It is a veritable master class in the cantorial art form: krechts employed with the natural ease of an everyday consonant, sweeping coloratura, and seamless tonal shifts all woven together into a singular masterpiece. To pick just one segment, I am struck by Rosenblatt's singing of the hatimah, the closing b'rakha, "who in His mercy restores Jerusalem." Given the high intensity of all that precedes it, I might have expected a dramatic finish filled with fast moving melismatic lines concluding with Rosenblatt's signature falsetto coloratura. Instead, Rosenblatt sings these closing words softly and slowly, and in a middle to low register. Why? Perhaps he is returning to the humble pleading of the opening lines. Or maybe he is making an emotional statement that he has poured his heart out and has no more left to give. Whatever the intention, there is no doubt that Rosenblatt does not merely sing a nice musical version of the text, but aims to evoke the meaning of the liturgy accurately and sincerely.

To try to describe the rest of the setting in detail would take volumes. Musically, it is beautiful and varied. It is a veritable master class in the cantorial art form: krechts employed with the natural ease of an everyday consonant, sweeping coloratura, and seamless tonal shifts all woven together into a singular masterpiece. To pick just one segment, I am struck by Rosenblatt's singing of the hatimah, the closing b'rakha, "who in His mercy restores Jerusalem." Given the high intensity of all that precedes it, I might have expected a dramatic finish filled with fast moving melismatic lines concluding with Rosenblatt's signature falsetto coloratura. Instead, Rosenblatt sings these closing words softly and slowly, and in a middle to low register. Why? Perhaps he is returning to the humble pleading of the opening lines. Or maybe he is making an emotional statement that he has poured his heart out and has no more left to give. Whatever the intention, there is no doubt that Rosenblatt does not merely sing a nice musical version of the text, but aims to evoke the meaning of the liturgy accurately and sincerely.

Could you imagine someone singing this rendition of "Rachem No" when leading Birkat Hamazon? It's not very likely. And not very practical in most settings, be it an intimate dinner at home or in a dining hall full of hundreds of hyper campers. Yet we can still take a lesson from Rosenblatt. Even while maintaining the spirited, raucous singing we are accustomed to--which I should add, I love--it would still do us some good to integrate even a small fraction of the kavanah with which Rosenblatt sings "Rachem No." Would taking into consideration what we are saying distract from the intensity of our singing Birkat Hamazon? I say "no." If Birkat Hamazon inspires the energy and ruah we are accustomed to primarily through the music, how much more of an intense experience would it be if we called to mind--or were even aware of--the deep theological statements and collective yearnings found in the words? I think we can draw inspiration from Rosenblatt's emotive singing while maintaining the unbridled ruah we all love.